The Blood TrailBill Claspell

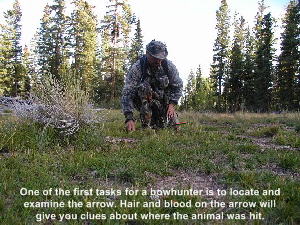

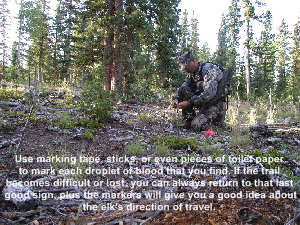

There is a saying that, in big game hunting, the real work doesn’t actually begin until you have the animal on the ground. That’s true…kind of. There is no doubt that hunting for big game such as elk, Colorado’s second largest big game species, is a challenge that requires a lot of preparation, sweat, and long hours in the woods. And it’s true, too, that packing one of those animals out of the woods can become a huge chore, especially when you knock one down in the back country and have to bring it out piece by piece. But there’s a time in between the shot and admiring the animal on the ground when the work is less physical, but just as critical, to recovering your game. Blood trailing is, in my opinion, one of the most important, yet least understood aspects of big game hunting. Important, because the things that you do immediately after the shot can greatly increase, or decrease, your ability to find your animal once it’s down. Anyone who has ever harvested a big game animal knows the excitement and adrenaline rush that comes after the shot. These emotions, left unchecked, can cause people to do some mighty strange things or react in ways that can jeopardize game recovery. I heard a story once of two bowhunters who had stalked in close to a nice bull. The stalk had taken several hours and the hunters finally worked their way in close to the bugling bull. Finally, when the shot was presented, one archer raised his bow and fired an arrow that caught the bull in the boiler room. The other hunter, in his excitement, stood up and yelled, “Yea! You got him!” The bull, of course, bolted and ran full speed into the dark timber and over the next ridge, automatically compounding a trailing job that should have been relatively simple, and making the packing chore that much longer. I’ve also heard of other hunters who, after making a marginal hit on an animal, immediately took up the trail and never recovered the animal. During the 2004 archery elk season, my young buddy Travis was able to make a nice shot on a cow elk at 10 yards. The cow had come in to our setup, and once the shot was taken, she began to run. I immediately used my cow call to stop her, and not even knowing that she was hit, the cow put her head down and started to feed. Thirty seconds later, she went down for good. The total blood trail distance was less than ten feet. Although this was Travis’ first archery hunt and he was overjoyed at making a great shot, keeping his emotions in check allowed us to keep the cow relaxed and contributed to a quick, clean kill and fast recovery. But what about those animals that don’t stop or go down within sight? Those are the animals that must be trailed, and the actions that you take then can be crucial. The number one critical element in successful blood trailing is this: Take ethical shots. Period. Risking a shot through thick cover, or shooting at a low percentage area, such as the hind quarters or paunch, will only result in a wounded animal, a long trail, and the low probability of recovery. When I prepare to take the shot, I carefully examine the lane that I’m going to be shooting through and pay particular attention to small limbs that might deflect the path of my arrow and knock it off course. Once I’ve decided that the lane is clear, I wait for the animal to present a perfectly broadside, or slightly quartering away, shot angle. This type of shot angle, for archers, guarantees the best penetration with the highest probability of striking the vital organs. Rifle hunters who wait for this shot angle, too, will have the highest rate of success. I’ve had some extremely close calls with animals that have come directly in to where I was set, and never presented me with an acceptable shot angle. While it has been tempting to take a low probability shot on occasion, I never have, and those animals lived to see another day. This is much more acceptable to me than wounding an animal and risk not recovering it. Once I have taken the shot, I sit quietly and watch the animal. This is important for several reasons. I can evaluate the shot placement, I can watch the animal’s direction of travel and for the animal to go down, and, most importantly I avoid spooking the animal into overdrive. Evaluating the shot placement is critical. A hard hit animal won’t go far, but a marginally hit animal may travel quite a distance before it beds down and it may take a little longer for that animal to succumb. So determining how well the animal is hit will dictate how long I wait before taking up the trail. For hard hit animals, I will usually wait a minimum of thirty minutes before beginning the trail. For a marginally hit animal, I may wait an hour or more, depending on the shot placement, and will not return to the trail without help. Having another experienced blood trailer to help track the animal, or to help with looking far ahead for signs of the animal, can be very helpful. Taking up the trail of a wounded animal requires stealth and patience. I begin by marking the place where I was at and where the animal was standing when the shot was fired. I use orange surveyors ribbon to mark that area so that I can return to that spot in the event that the trail becomes lost. When I get to that spot, I spend some time interpreting the tracks that are left, examine the area for blood, and being an archer, I’ll take some time to find my arrow. Once I find blood, I evaluate it, too. Blood that is dark red may indicate a liver or muscle hit. Lighter pink colored blood that sprays to the sides of the trail usually indicates a lung shot, and blood with traces of green slime means a paunch shot. Liver, lung, and heart shot animals expire quickly while paunch and muscle shot animals do not. In either case, I’ll take a lot of time to slowly trail the animal and be wary of my surroundings in the event that the animal leaves its bed and allows time for another shot. Blood trails can become very difficult to follow, especially in leafy or extremely dry conditions. Following the trail left by the animal, I will remain at each spot with blood sign, mark it with surveyor’s ribbon, and will look ahead to find more blood before I move forward. If I lose sight of blood and cannot locate it from the place where I’m standing, I’ll mark that last sign with some ribbon before moving forward. Animals will typically move in a straight line unless some obstruction blocks their course of travel, so I’ll begin moving from the last sign, in a straight line, until I find more blood. Looking at the back trail, marked with ribbon, can give me a good indication of the direction that the animal was traveling in the event that I stray off course. If I’m unable to locate any blood sign, I’ll use a fan pattern search, beginning at the last sign, and will move outward until I find more. Continuing in this way, sometimes on hands and knees, I can search for tracks and blood sign that will give me an idea about the animal’s direction of travel. It has been my experience that an elk that travels over 150 yards after the shot is not hit very well. Animals like that need to be given ample time to bed down and so, in those cases, it’s not unthinkable to let an elk lie for several hours before taking up the trail again. The last thing that you want to do in such a situation is push the animal hard and move it out of its bed. A five or even six hour wait before taking up the trail will increase your odds of finding a marginally hit animal. Elk are tough, but most won’t go far after they’ve been hit, especially if you do your part to keep them calm after the shot. Evaluate the shot, be honest with yourself about the shot’s placement, take your time and proceed with stealth and patience. Every trail leads somewhere, and with proper blood trailing techniques, you will be skinning and quartering before you know it. And that’s when the real work begins. Those who seek knowledge kill more elk than those who do not! For a lot more information on elk and elk hunting please consider purchasing one or all of my top-selling books on the subject.Click here. |

|

This document may contain copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. ElkCamp.com is making this information available for the purposes of criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research. We believe that this constitutes a 'fair use' of the copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Law.

|

ElkCamp is a registered trademark. All use is reserved. |